“Systemic Effects of Metal Exposure in Clinical Practice: Protecting Patients and Optimising Outcomes”.

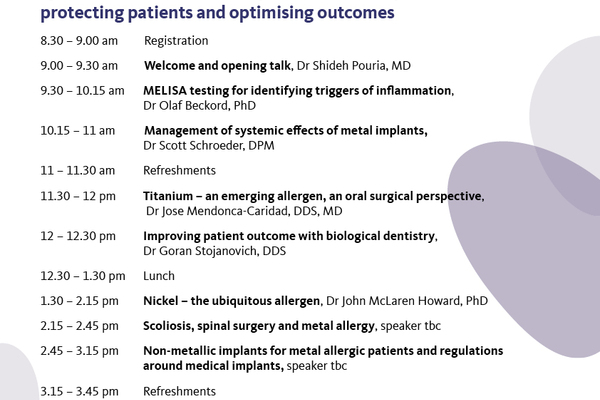

A summary by Dr Shideh Pouria.On 16 November the British Society for Ecological Medicine held a conference in London exploring the concept of metal toxicity and allergy as a much-overlooked factor in modern diseases. The conference was held jointly and dedicated to the memory of Professor Vera Stejskal, who passed away last year. Prof Stejskal was a pioneering Swedish immunologist and the inventor of the MELISA blood test for diagnosing metal allergy.*

Speaking at the conference were medical, surgical and dental professionals, many of whom have found the MELISA test invaluable in their practice, as well as scientists who have used the test to investigate the mechanisms and effects of metal toxicity. Overall, the day provided an eye-opening series of lectures on what appears to be a frequently overlooked source of ill health and disease.

The conference began with a presentation by Dr Olaf Beckford, a chemist, who together with Prof Stejskal set up the MELISA lab in Neuss, Germany. Dr Beckford gave an overview of the wide range of symptoms that may be caused by metal hypersensitivity, including fibromyalgia, muscle pain, chronic fatigue, autoimmunity, gastrointestinal problems, dermatitis, chemical sensitivity, headaches, cognitive dysfunction, and depression. Metal hypersensitivity causes inflammation, which is a central factor in many chronic diseases, including heart disease, Alzheimer’s, and cancer.

Sources of metal exposure include dental fillings and implants, medicines, cosmetics, foods, vaccines (in which aluminium and mercury are used as adjuvants), smoking, piercings, and medical devices such as pacemakers. Dental restorations alone can include mixtures of various metals such as mercury, gold, palladium, tin, silver, nickel and more. Macrophages act as transporters of metal ions throughout various tissues via the blood and lymphatic systems. Often potentially toxic metals compete with other beneficial minerals or for transport systems – for example, titanium and iron or zinc and nickel. Dr Beckford explained that even though metals may exert toxic effects in biological systems, MELISA testing does not measure such toxicity: instead it is a means of assessing metal allergy or hypersensitivity.

Several speakers presented cases of patients with serious health problems who made remarkable recoveries after the source of metal sensitivity and toxicity was removed. Dr Schroeder is a Washington State-based surgeon who in the last ten years has removed over 1,000 metal medical devices. He presented cases of extraordinary improvements in his patients’ health as a result of his interventions. This included included a patient with fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue, migraines, and rosacea. The onset of symptoms had followed surgery in which stainless steel and subsequently titanium screws were placed in her foot. MELISA testing came back positive for nickel, titanium and vanadium allergenicity. After the hardware was removed, she recovered her health fully, as attested by a voice recording that was played to the conference attendees.

Dr Schroeder also presented evidence, which showed that implants consisting of two different types of metals (e.g. stainless steel and titanium) can be far more problematic when used in the same patient. This is because an electric current is set up between the two metals, leading to corrosion and dispersal of one or both metals throughout the body and resulting in widespread systemic toxicity. This can take place even if the two different metal implants are widely separated within the body.

Dr Jose Mendonça is director of the Head and Neck Surgery Unit, Adult Stem Cell Therapy Unit at POLUSA Hospital, Galicia. He spoke about the shifting paradigm regarding titanium, which has historically been viewed as a biocompatible and safe material for use in dentistry and implants. However, more recently, a growing number of studies document side-effects such as allergy and corrosion. This new perspective has to be seen in the context of the increasing possibility of contact with titanium, via (for example) titanium dioxide in food additives, sunscreens, cookware and medicines as well as to other compounding factors such as exposure to electromagnetic fields (EMF).

Titanium-related issues observed by surgeons and dentists may include infections, allergies, osteolysis, bone resorption and neuropathy. Dr Mendonça explained that toxic metals tend to accumulate in the jaw. From there, the vascular system transports them into the brain, causing neuro-inflammation, cognitive dysfunction and other symptoms. In his practice he showed how the removal of titanium implants from affected patients and replacement with implants made of zirconium improved patient outcomes. He mentioned cases of Alzheimer’s that have been ameliorated after titanium dental implants were replaced with ones made of zirconium.

In cases of patients with reactions to dental implants and as a resultant damage to the jaw, Dr Mendonça has been able to regenerate the affected tissue using adult stem cells derived from bone marrow, along with tissue matrix proteins and growth factors (cytokines). Clearly this therapy should be made widely available to regenerate damaged and necrotic tissue in a number of disease conditions.

Dr Goran Stojanovic is a biological dentist based at the NDU Clinic in London. He spoke of the wide array of metals commonly used in dentistry and said awareness is growing among dentists and patients of the toxic and allergenic potential of such metals within the oral cavity and also systemically. He discussed the case of a teenage girl presenting with fevers, blisters, and excruciating pain while chewing after dental orthodontic treatment. One of the differential diagnoses entertained by her doctors was leukaemia. She was found to be allergic to the nickel in her dental braces. Immediately the braces were removed, her symptoms vanished.

Dr Stojanovic discussed more biocompatible alternative materials available, such as zirconium implants, ceramic inlays, and glass ionomer and composite fillings. He outlined the protocols used to safely remove toxic materials such as mercury amalgam fillings. He emphasized the importance of using barriers and other protective methods to prevent further exposure to the patient and dental staff alike.

Dr John McLaren-Howard, of Acumen laboratories, spoke on the topic of nickel as the “ubiquitous allergen”. He demonstrated how various aspects of nickel sensitivity can be diagnosed in different ways. Dr McLaren-Howard said about 25% of people with skin sensitivity to nickel who pass through his lab show positive responses to both MELISA and ACUMEN.

He highlighted also the important interactions between calcium and nickel: for example, many cell signalling pathways use changes in intracellular calcium as a messenger and nickel is one of a number of potential toxins and allergens that ‘piggy-back’ onto that mechanism. Nickel and intracellular calcium changes affect important cellular mechanisms, including mitosis. Nickel also accumulates on hormone receptor sites.

Nickel has long been recognised as a known carcinogen, but less well known is that it has a strong relationship with heart attacks. Research has found increases in serum nickel following heart attack. It is possible that the nickel is stored in mitochondria in heart muscle and released during the heart attack. In general, urine nickel increases are useful biomarkers, but nickel found in more specific tests shows greater clinical significance, e.g. when it is found as a DNA adducts

Sources of nickel exposure include stainless steel cooking vessels, medical and dental implants and devices, body piercings, smoking, vehicle exhaust, and many foods. Supplementing with vitamin C during meals and a diet high in iron inhibits nickel absorption.MELISA team member Mrs Rebecca Dutton runs support groups for patients affected by scoliosis (http://www.understandingscoliosis.org/). In her presentation, she discussed how a significant proportion of patients who undergo scoliosis surgery have been found to be allergic to their spinal hardware. She suggested that one of the underlying causes of scoliosis could be exposure to metals in the first place (the link between misshapen spine in fish and mercury exposure is already known). Sources of mercury exposure include thimerosal, the preservative used in childhood vaccines until it was (mostly) phased out in 2004. She put forward the case for routine preoperative metal allergy testing and gave examples of non-surgical treatments for scoliosis or the use of non-metal spinal hardware (such as carbon-coated implants) as alternatives to metal hardware.

Mr Simon Ellis is an independent consultant in trauma and orthopaedic surgery who specialises in knee surgery. He spoke about the problem of metal allergy in relation to joint replacement. He said that over the last ten years it has become clear that there is a group of patients for whom conventional joint replacement using stainless steel components containing nickel is inappropriate. Negative reactions include synovitis, pain, stiffness, infection, necrosis, and skin problems. However, metal hypersensitivity as an explanation for poor outcomes from knee surgery was highly controversial among surgeons, with the majority denying that it could explain poor functioning of a knee replacement. In spite of this reluctance to acknowledge any problem, there are a growing number of lawsuits following serious reactions such as necrotic tissue at the sites of knee replacements. Mr Ellis uses MELISA testing pre-operatively to identify metal hypersensitivity in patients with indications of sensitivity, for example, a skin nickel allergy. He also uses it post-operatively in patients with implant failure. He favours the use of nitride-coated implants as an alternative to metal.

The final speaker was Christopher Exley, professor in bioinorganic chemistry at the Birchall Centre, Lennard-Jones Laboratories, Keele University (UK) whose research has focused on the ecotoxicity of aluminium. Prof Exley discussed aluminium, a systemic toxicant, as an adjuvant in vaccines. He pointed out that aluminium adjuvants are not separately tested for safety and approved by regulators. Only the complete vaccine is approved. In addition, aluminium adjuvants are administered to the placebo group in vaccine safety trials. Thus there is no way of identifying potential adverse reactions to these adjuvants in regulatory safety trials.

Prof Exley said that vaccine experts have no real idea how aluminium adjuvants function. They are included in vaccines to ensure that the patient produces an optimised immune response when they are injected with a vaccine, but he said that this response was in truth a response to aluminium’s toxicity, which causes damage at the site of injection. This results in infiltration of immune cells at the site of tissue damage, which increases the possibility of an immune response to the antigen. He suggested that serious adverse events following vaccination might be caused by aluminium adjuvants in susceptible individuals.

Prof Exley also described findings from one of his most recent publications which showed alarmingly high levels of aluminium in sections of brain taken from patients who had died from complications of autism spectrum disorder. These observations further call into question the safety of aluminium adjuvants. During the discussion following his presentation Prof Exley said that it was possible to design a safe aluminium adjuvant – though it remains to be seen if he will be invited to do so!

The day ended with a final tribute to Vera Stejskal in the form of excerpts from a recording of a talk, which summarised rather aptly the topics covered during the course of the day. The take-home messages from this highly inspiring and illuminating day were:

- Metal hypersensitivity is on the increase due to proliferating sources of exposure and potential co-factors such as EMF exposure

- Steps should be taken to avoid exposure in the first place

- Patients showing symptoms that could be due to metal hypersensitivity should be tested using MELISA and other indicated methods

- Patients who have had reactions to metal hardware or other exposures should be tested for hypersensitivity

- Metal implants and dental materials that are causing problems should be safely removed, or replaced using non-biologically active materials

- Toxic metals (e.g. mercury, aluminium) used in vaccines may pose health risks to susceptible individuals

- Appropriate detoxification methods should be employed to help patients recover their health.

Recordings of the conference proceedings are available to purchase as a USB flash drive from the BSEM website here or can be purchased as a downloaded from Vimeo here

______________________________________________________________________________________

*(http://www.melisa.org/2017/10/13/in-memoriam-vera-stejskal/)